This post pulls together some thoughts and ideas on reflection and feedback. It draws on some great coach conversations, research on various professional’s reflective practices and the world of contemporary dance. Quite a range of inspiration.

Form versus Free-Form

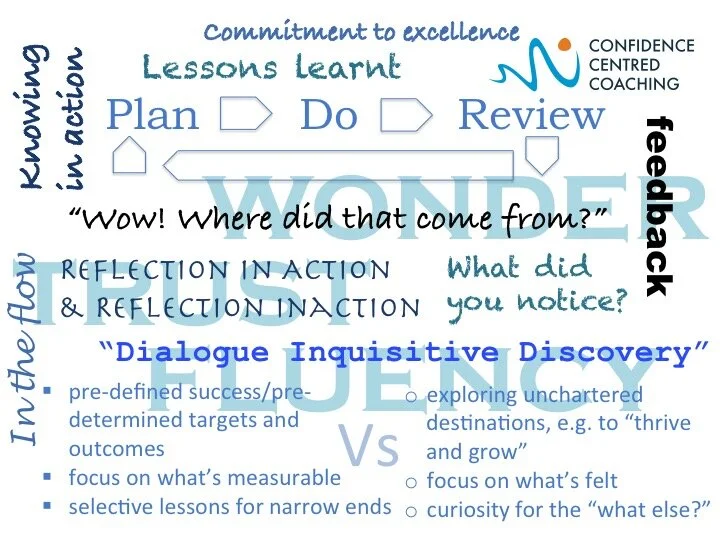

I know pretty much every coaching manual and standard course will at some point go through the formula Plan – Do – Review. And of course the importance of reflecting back on what went well, what could be done differently, what to learn for next time is undeniable. But it’s the form – and in some respects the formality – of reviews and reflections that I sometimes wonder about.

I recall seeing a lead coach summoning the other coaches involved in a club session so he could gather feedback before they were allowed to go. “Give me three points from the session that went well or could be improved” was more or less his command, clipboard in hand and pen at the ready.

I kept out the way but could sense their unease at being put on the spot. And thinking back to the incident (the coaches quickly learnt to make fast get-aways so the inquisitions didn’t get repeated), I wonder about our positioning as coaches in reviews and reflections.

Are we there as authority figures in charge of gathering so many must-dos and faults to be put right next time? The guardians of what counts as permissible knowledge. Or can we be curious guides, looking to explore what (if anything) might have struck each coach, enquiring how each felt without a “room for improvement” judgement, each observation triggering further “I wonder what was going on there?” type considerations? The latter feels like a richer mine of ideas of things to do differently. And I believe the same principles and approaches work for our own self-reflection.

Wouldn’t it be great if we got to such an easy, trusting place – both individually and working in a team – where there is a natural, almost free-form fluency in reflecting back and learning from our coaching moments? That’s what the rest of this post feels it’s way toward: an easy, natural and rich reflection, first in the very moment of our coaching and then after the event.

In the Moment 1: When Things Don’t Go Right

I’ve been tuning in to some engaging conversations between two leading, yet unassuming coaches: Jenny Coady and Nick Levett. In their regular Coach Conversation they chat freely, share experiences, ask each other inquisitive questions and come up with super insights. Great to listen in to and reflect on!

In one of the recent Conversations, Nick talked very openly about a session he led where, despite those around him complimenting him on how well it had gone, he was left feeling that it just hadn’t worked – maybe not the “disaster” he first judged himself to have presided over but still a sense of knowing things had gone awry.

At the heart of it seemed to be moments when he could see the prospect of learning points evaporating amidst a busy, overloaded set of exercises (brilliant though the ideas behind them sounded). He openly recalled what was happening in his mind, realising in the moment of all the frantic activity that something needed to be cut back but feeling it was too late to call out a change.

This took me straight back to times I’ve held very similar feelings – of realising in the moment that the focus and learning points of a session are all slipping away but being hesitant or unable to step in and make a change. The longer my inaction, the greater sense of unease at the unfolding chaos and a sense that I’m not coaching well enough. Reflection inaction. A pretty awful, undermining feeling.

As an example, I can see them now. On the field, a group of young boys I was tri coaching. The session rapidly descended from them having fun with a set of run drill exercises I let each boy in turn choose and take the lead to demonstrate, to just mucking about and taking the piss! (An advanced coaching term.) And in my head I was battling with a sense that I should be doing better than this, yet knowing that it was precisely because I’d handed over the choice to the young triathletes that it was becoming chaotic. Jenny summed up Nick’s – and my – dilemma as “are we getting creative in the chaos or is the chaos hindering the creativity?”

Perhaps one just has to accept that if you’re aiming for creative, interactive ways of coaching some things will work and some won’t; that this doesn’t signify “disaster” or a judgement on yourself as a coach; while holding in mind the bottom line of keeping it safe. (In my example, no one was harmed though my pride was a bit bruised.)

And maybe we just have to experience such moments of things not going right to be more attuned to the moment and, most important, trusting ourselves and those we are coaching: either to let things run their course, knowing there may still be value for others; or to step in, acknowledge something isn’t working, take a pause and together see how to refocus.

In the Moment 2: When Things Go Right

And what about when things are going well? Here’s where the idea of reflection in action comes to the fore.

“know-how is in the action… [not in] rules or plans which we entertain in the mind prior to action. Although we sometimes think before acting, it is also true that in much of the spontaneous behaviour of skilful practice we reveal a kind of knowing which does not stem from a prior intellectual operation.”

The term comes from a pioneering study by Donald A. Schön of how architects, psychoanalysts and other professionals think, problem-solve and make decisions in each of their very different practices. He set out to debunk the popular conception of experts applying their accumulated knowledge to each problem or challenge before them as if in a rational, thought-filled way. Instead, Schön saw something far more intuitive, creative and tacit – an in the moment “knowing in action” that often the professional couldn’t put into words, only able to rationalise after the event.

In other words, it just happens. In coaching, these are those wonderful moments in which we are so absorbed in the act of coaching and the people in front of us that it is as if there is no space for thought. Here’s where we might instinctively and spontaneously come up with creative ideas that just seem totally in tune with the moment and those we are coaching. And afterwards we might go home and wonder “wow – where did that come from?”

I had a super conversation with a close friend and wonderful triathlon and swim coach recently where we talked about what is happening when we are at our most fluent in our coaching. The creativity and sheer fun of sessions where we are immersed in what is unfolding before us and able to trust ourselves to go with a flow was a big theme.

Interestingly she also highlighted something of a dilemma. She spoke of being poolside, completely focused and attuned to the needs of the young swimmers she is coaching and trusting her instinctive judgement, just knowing or sensing in that moment who is ready to move up to the next group and who needs some extra support. Yet she can then find herself under pressure to articulate this to disgruntled parents (not that some would accept even the most objective, rational reasoning). It is as if the words for reflection only come after the knowing in action.

Feedback

So what about the form of reflecting, reviewing and seeking feedback after the event? I’m drawn to a powerful feedback model, designed for artistic work in progress by world renowned choreographer Liz Lerman, called the Critical Response Process.

Now, there is an obvious difference with coaching. Liz Lerman’s respondents are an observing, attentive audience. Our engagement is with the actual participants, whether other coaches or our athletes. Yet the key principles in her model seem to me highly relevant and helpful in seeking feedback from others and how we review and reflect on our own performances as coaches.

The first key principle is that there’s a dialogue: in Liz Lerman’s case between the artist presenting their work in progress and the responders. It’s a two way process of asking for and receiving, skilfully questioning and offering feedback. Second, there’s a depth of inquisitiveness: the responder being guided to think about how they were impacted by the work, what was meaningful or evocative, rather than complimenting or judging. And thirdly, the importance of discovery: the process guides learning for both the artist and the respondents, based on a shared commitment to improvement, rather than a take it or leave it evaluation of what’s good or bad, what worked and what didn’t.

You can see a brief outline of the four steps in the model and the roles of the presenting artist, respondents and facilitator here. I believe we can apply the basics of her approach to reviewing and seeking feedback after a session or event, in the following way:

no jumping straight to what needs to be done differently, instead first finding out what might have struck each coach and/or athlete, how they felt, what it did for each of them, asked in a curious, open way

asking about specific elements of the session that we were particularly aiming to emphasise or want to know how coaches/athletes experienced

as part of the dialogue, showing ourselves open to the other coaches and athletes asking about one or other feature, in the process demonstrating our commitment to understand and learn more together, rather than seeing it as a challenge or judgement

and only then, open up to suggested alternatives or different ways of achieving our common purpose.

It works! And all this can be done in what feels like a natural conversation, with no one put on the spot (and no need for a clipboard and pen).

And I believe we can apply the same steps to our own self-reflection. Were those young boys really taking the piss (in truth a rather dismissive, defensive, coach centred way of looking at things)? Or did they actually go away having some much needed down time while knowing how to play with a particular drill, doing it wrong ready to do it right next time? It could have been. I’d have to have asked.

As always, please leave your own reflections in the Comments box below - following the Liz Lerman model, I’d really like to know what struck you and any connections you see to your coaching?